link: plan and description | “But how comfortable do the people feel who work in such surroundings? As part of an effort to improve its facilities, one large pharmaceutical corporation, Merck & Company, surveyed two thousand of its office staff regarding their attitudes to their place of work - an attractive modern commercial interior. The survey team prepared a questionnaire that listed various aspects of the workplace. These included factors affecting appearance, safety, work efficiency, convenience, comfort, and so on. Employees were asked to express their satisfaction, or dissatisfaction, with different aspects, and also to indicate those aspects that they personally considered to be the most important. The majority distinguished between the visual qualities of their surroundings - decoration, color scheme, carpeting, wall covering, desk appearance - and the physical aspects - lighting, ventilation, privacy, and chair comfort. The later group were all included in a list of the ten most important factors, together with size of work area, safety, and personal storage space. Interestingly, none of the purely visual factors was felt to be of major importance, indicating just how mistaken is the notion that comfort is solely a function of appearance or style. “What is most revealing is that the Merck employees expressed some degree of dissatisfaction with two-thirds of the the almost thirty different aspects of the workplace. Among those about which there was the strongest negative feelings were the lack of conversational privacy, the air quality, the lack of visual privacy, and the level of lighting. When they were asked what aspects of the office interior they would like to have individual control over, most people identified room temperature, degree of privacy, choice of chair and desk, and lighting intensity. Control over decor was accorded the lowest priority. This would seem to indicate that although there is wide agreement about the importance of lighting or temperature, there is a good deal of difference of opinion about exactly how much light or heat feels comfortable to different individuals; comfort is obviously both objective and subjective. The Merck offices had been designed to eliminate discomfort, yet the survey showed that many of the employees did not experience well-being in their workplace - an inability to concentrate was the common complaint. Despite the restful colors and attractive furnishings (which everyone appreciated), something was missing. The scientific approach assumes that if background noises are muffled and their direct view controlled, the office worker will feel comfortable. But working comfort depends on many more factors than these. there must also be a sense of intimacy and privacy, which is produced by a balance between isolation and publicness; too much of one or the other will produce discomfort. A group of architects in California recently identified as many as nine different aspects of workplace enclosure that must be met in order to to create this feeling. These included the presence of walls behind and beside the worker, the amount of open space in front of the desk, the area of the workspace, the amount of enclosure, a view to the outside, the distance to the nearest person, the number of people in the immediate vicinity, and the level and type of noise. Since most office layouts do not address these concerns directly, it is not surprising that people have difficulty concentrating on their work.” | Witold Rybczynski

HOME - A Short History of an Idea

1986

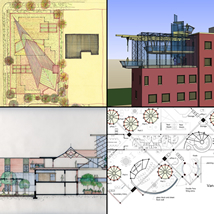

pp 226-228 | | | This observation by Rybczynski is over 16 years old. Although many things have improved in the increment, office interiors as a system, remain fundamentally the same. There are a number of primary design assumptions that have not been challenged and that continue, no matter the cost and apparent amenity of office environments, to produce unhealthy and inadequate workplaces [link: manifesto]. At the time that he published his book, we built the Capital Holding Design Center [link]. Like the Orlando environment before it, and the work that followed [link], we explicitly addressed the underlying issues of workplace dissatisfaction: the worker cannot control the essential conditions of their surround, temperature, sound, privacy, real-time configuration, light levels, personal customization; nor, does the typical work environment create place and relate to someplace. The typical environment - over-lit, rigid, one size fits all, unforgiving materials - is a creature of averages; it does not respond to the individual; it is a high class work prison. Nor, does it establish an urban landscape that has both exterior and interior amenity and identity. Lacking in material quality, failing to create a variety of different sub-climes and unique niches, the typical modern workplace fails to meet basic human requirements. Not only is this the condition of the vast builder-designed environments that were never intended to have distinction, it is the result of the majority of high-class architect-designed premium environments where design and visual tricks overlook and overwhelm true comfort. The vast majority of modern architecture makes great pictures but offers little the the way of true utility or comfort. The typical office building is not a place that many have any true like or passion for. Automobile manufactures do a better job. | | The geometry of the building is square on square with the 30/60 degree triangle layered on top of it. The second geometry emerges out of the first as the building progresses from the north end to the south. The building presents to the north and west streets a conventional form and proportion with enough hints, however, that something different is going on inside. That “something” grows to become the major expression at the NavCenter Radiant Room. Materials stay consistent thereby providing an integrating armature. Brick, concrete, glass and tile make up the major palette. The exception being the plastic and colored glass used in the rising triangular roof sections of the emerging geometry. | Structure and Method of Construction | | There are two structures involved in this project: one is conventional masonry pier on grade beam with coffered concrete roof and the other a light-weight steel fabricated, plastic-glass structure. Each of these follow their own parallel design-build paths that converge during the field erection process. | | These two processes will be integrated much in the same way as the field masonry and prefabricated cantilevered arms are intended in my Bay Area Studio project [link]. Where the two structures come together, collars will be fabricated to embed in the field-built masonry in order to insure the ultimate fit of the fabricated components. These collars are both structure and finish and fit into the overall grammar of the building. | | The conventional field construction is designed to be built by a small integrated team of mixed trades in a continuous process from North to South. Grade beams and piers, pipe columns and masonry, “upside down” coffered roof deck will flow as a continuous process until complete This will be require about two and a half weeks using small crews. Necessary electrical and plumbing rough-in will be done at the same time. Floor slabs will go in last. The steel lolly columns for the steel-plastic-glass roof structure will go in at the same time. The erection of the prefabricated roof sections will follow the conventional work. The entire sequence from exposing the site to effective close in will take about 30 to 45 calendar days of work the major variable being weather. The time to prepare the site cannot be estimated until underground conditions are better known. However, given the size of the property, 7 to 10 days should be sufficient. | | The concrete roof is the same as a typical parking garage except in this case the “coffers” are on top. They become the planting beds for the roof planting. | Prior Art and Historical Fit | | There is a great deal of history around this building and the design is deliberately sensitive to it. There are forms that work in this kind of an urban context and the building employs them without being enslaved to them. As a material and as a form, the brick retaining walls, piers and wall screens reflect the traditional urban architecture found in the area. The landscaped roof, however is the first point of departure. While traditional in form, three aspects standout: first, the brick piers stop short of the soffit line; the roof rides on pipe columns with a band of glass separating the soffit from the top of all masonry elements except a few vertical ones that rise chimney-like above the roof. Second, the roof has a wider than usual cantilever in all directions; this, with the glass ribbon, gives it a sense of independence and floating. Third, the landscaping itself which is abundant and spill over the roof and down through open coffers to be met by the ground landscaping reaching upward. The roof becomes an Armature of green. These traditional and new elements create a mutual tension and reinforce the theme of the building [link]. The overall “face” to the street is one of repose; a landscape with terraces, ramps and steps leading into the “protected” (in the sense of sheltered) interior. | | Earth-sheltered building has evolved over the last 30 years and is now a reliable technology. Employing the coffers will provide a means for easy waterproofing and isolate any future problems for repair by avoiding large expanses of roof. It also allows separation between plant types so that specific landscaping pieces can be more readily located in their appropriate places. | | Traditional cities and buildings spent more attention on the interface between the street and a building. There was far more interaction than that of the modern car culture where entering buildings through ugly parking garages devoid of ceremony is common. The medical center of which this navCenter is to be associated, avoided this all too ubiquitous mistake and put a great deal of effort into this aspect of their new addition [link]. The NavCenter facility, also, have to take care in this regard. Not only in the logistical sense but in the regards the “message” that the building sends to the street. Cities are places of interaction - this is what makes them work. A city that does not invite walking works poorly and gives up a large measure of what it is. This is an urban setting and the building has to respond to it while, at the same time, maintaining security and legitimate privacy. Several years of operating knOwhere Stores taught us a great deal in this regard. This design is composed of “layers” of increasing privacy made of by the positioning of walks, patios, doors and interior areas. the building protects while keeping an open aspect to the world. It encourages interaction but sends strong signals regarding what is appropriate. These are deep Pattern Language principles largely ignored today with abrupt openings and guard stations substituting for a measured entry and the expectation of social grace. The appropriate use of electronics makes it possible to have open environments that are also safe. | | With a skilled design-build team, employing fast-tracking methods, this building is designed so that it can be built in four months from permit and a clean site to move on. This schedule can be accomplished by a selective mix of field-built and prefabricated components. The building is designed so that the cycling of trades throughout the construction process is efficient and the common practice of pulling trades on and off the job, as the work progresses, is eliminated. It can be tightly phased using small crews, working continuously, following one another, working through the building in a measured and scheduled way. This is rarely accomplishable with a small project unless build-ability is designed-in to the concept of the building. | | The building schedule is as much the basis of the contracts as are the drawings and specifications - not “you will be done by a certain date or there will be penalties” kind of contract; a day-to-day schedule of all work of all trades. The problem of how the building is to be built is an integral aspect of the design, pricing and contract process and the agreements make everyone responsible for the result. In this, and in other cost strategies outlined below, the building must be totally solved before starting. Today, the design is solved “on paper” and the building sequencing issues are left to the winning bidder after the contract award. Often, in small projects, they are never solved - the workers just blunder through it as best they can. The quality of field supervision can effect a sub-contractor’s cost by as much as 60%. Since, with conventional methods, there is no way for a sub to even know going in to a project what real conditions will prevail, defensive scheduling and pricing are the only alternatives. Since work does tend to expand to the time allocated this hidden margin is usually eaten up by lack of schedule focus, proper field supervision and inattention. Control time and you can control costs and achieve quality. | | I will not address specific costs here; my focus is on what approaches in the design strategy make this building intrinsically economical and affordable. Most buildings cost too much. The basis of these costs are rarely found, challenged and eliminated. Instead, some feature is usually eliminated - usually some “luxary” that directly relates to the quality the building’s users actually touch and experience. Very few buildings are priced, at the detailed level, on a true time and material basis. Fewer still are scheduled and managed to those estimates with feedback to the pricing function. Bids are used as a basis for selecting contractors; this is a dangerous practice based on assumptions that bear little relationship to reality. Knowing costs on the scale of cubic/square footage and other unit measures does not direct attention to where the majority of effort is wasted. Unit costs are sums; they are convenient for pricing a project but do not illuminate where time and effort is really spent. Waste is primarily found it four areas that operate at a completely different scale than these units measure: first, the sequencing of work and its impact on the overall time-to-build which generates a long list of rarely measured costs; second, the micro steps that make up a unit cost and the understanding of efficiency at this level; third, the costs intrinsic to specific details and combinations of materials which can vary wildly from region to region and design to design. The fourth is the most difficult to understand. This is standard practices in a field dominated by ignorance and urban myths. These practices range from the way that drawings are done, to construction practices which are economical only because of ubiquity not because of intrinsic economy. With everybody playing the same game, the lower cost of some providers - based on marginal performance improvements - is assumed to be “the bottom line.” Everybody is playing the same game; however, everybody is playing a different part of the game. Each tries to optimize their part while the system-as-a-system goes unattended. A classic tragedy of the commons. | | The first strategy is the separation between the structure of the building itself and the WorkFurniture interior. Not only does this eliminate many finish materials and trades, thus reducing complexity, it makes any future adaptive re-use of the structure easy. The building is finished, inside, exactly like its outside. Brick walls and piers outside are the same inside, as example. This gives the structure integrity; it also makes the interior of durable materials; it eliminates many finish materials which in turn reduces maintainence. The WorkFurniture solutions are easily moved, modified or removed as future requirements demand. The shell of the building creates many “universal” spaces of various kinds that can easily be adapted - without construction - to many different uses. This design strategy lowers capital costs and provides long-term, life-cycle cost economy. | | The second strategy is to employ a design/build, fast-tracking method that integrates construction documents with the actual “lean” building method this building was designed for executing. This involves a day-to-day story boarding process and detailed crew instructions based on the information they need for the sequence of work they are doing at a specific time. This eliminates huge amounts of wasted time and effort, ad-hoc figuring things out on the job and delays due to faulty scheduling. These hidden costs, are now ramped in the industry, assumed to be intractable and are built-in to all standard unit cost figures. By simplifying detailing, eliminating unnecessary trades, selecting builders - not contractors - and integrating crew, design, methods and documentation, unnecessary complexity and redundant overhead, profits and fees are also eliminated. A far greater percentage of labor and material (less wastage) is actually accomplished for the money spent. | | The third strategy is to employ local shop-fabrication for sub-assemblies and avoid sophisticated manufactured packages. Take the cost of overhead and advertising out by avoiding overly complex solutions that are not necessary if certain factors are designed-out. For example, a window that servers both viewing and ventilating functions is a complex devise. Separate fixed glass from vents. Local shops, especially in the mid west where this building is to be built, serve as third tier fabricators to several industries. In these shops you go in with your drawing, discuss it, make changes and pay for what you get - fast and economical and usually far less time spent then writing and expiditing a complex work order with a large complex corporation. Read the annual report of many of the premier components companies and do the numbers - work out what percentage of your dollar actually goes to what your are buying and using. | | These design-build methods were pioneered - and proven out - by me over 35 years ago. As much as 75% of the time and 45% of the cost of a typical small to meduium sized building can be eliminated. There is a cost, however. That “cost” requires tackling a project by rejecting virtually all of the corporate “best practices” typically in place to save time and money. No, I am not kidding. We have worked on almost identical projects where everything was the same, including the supervision and contractor, except the requirements of ownership. One took one month and $750,000 to build and equip a 12,000 square foot NavCenter and the other (the floor above two years later) 9 months and over 1.2 million dollars [link]. The techniques involved I refer to as the Swimming Pool Method because this is where I perfected them in the mid to late 60s [link]. I was able to do this because I had accrued extensive experience in all the major roles that make up the production of buildings and development projects and, therefore, could see, in concrete terms, what the system was actually doing (as apposed to the myth) and where the waste was - and, how much waste there was. What I discovered did not fit the conventional wisdom model - it still does not. I have also found, over the subsequent years, that few can believe these numbers even when confronted with executed projects that clearly reflect them. And, sadly, that many who do understand still choose the longer more expensive path rather that take the risk associated with breaking the conventional social-organizational rules. As the entire professional “organization” that builds is paid as a percentage of total cost, there is no incentive to do extra work and take extra risk in order to radically cut costs and, thus, one’s own fee-profit. It is my experience that few are really interested in the economy of building unless costs estimates for a given project put it at risk. Then, the easy expediency of sacrificing the quality of the building is the path usually taken. This, in fact, is deferring costs to the future. The customer plays and does not know it. The professionals are off with another “successful” building on their resume and no one is the wiser. The results are never correlated. There is no accountability in this system unless there is catastrophic failure of some kind. The feedback for this kind of failure merely drives people toward more conservative approaches. As a result, proposals to change the process meet great resistance. Creating organiztions with different expectations is a critical step before us [link]. | Landscaping and Energy Strategies | | This building is designed to “disappear” into its own internal and external landscaping. Virtually every surface of the building and its lot is planted. The superstructure of the building can be thought of as an armature [link] for planting. The scale of this is unusual in a workplace. The effect is of working in a park of trellis, patios and garden walls. The WorkFurniture sits inside this landscape and provides the intimate places for work and gathering. If there were a musical expression of this environment it would be something like Emmanuel De Falla’s Nights in a Garden of Spain. This space will seem cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It will reflect the seasons; at the same time, there will always be plant life in abundance. | | This landscaping approach is tied closely to the energy strategies of the building which will rely heavily on radiant heating, active and passive solar and earth-sheltering techniques. Air quality, which is often not good in modern buildings, is also a major consideration of this schema. The idea is to create four climate zones: the outside which will vary with the seasons (z-1); the exterior courtyards which will reflect seasons but will be temperature mediated in various ways (z-2); interior courtyards which will be fully conditioned and operable to open to the outside as feasible (z-3); and the strictly interior spaces which will be enclosed and enjoy natural light and dense landscaping (z-4) on the level of a sheltered garden. | | The typical approach to energy management has become one of resisting the flow of temperature rather than assisting in the movement of appropriate temperatures to appropriate places. The strategy of resistance leads to sealed off buildings with poor air quality and a sense of isolation from both nature and the street. These buildings are not engaged and subsequently neither are their occupants. This approach is neither efficient nor economical. Energy costs may be somewhat lower but so is work attendance and productivity. Natural systems adjust, they trade-off, they manage energy, they metabolite. Nature never requires that all parts of a body function at the same temperature, or at the same level, all the time. Systems that attempt this are not adaptable and cannot handle variability. And, nature pulls off energy feats that makes our technology look primitive. The energy strategies and use of this building is intended to be natural; natural in how it manages itself, in how it feels to the occupants - it is an organic response rather than a machine one. | | The basic approach is to first design the building as if it had not electricity and HVAC and yet had to be as comfortable as possible and then use modern technology to augment this basic natural strategy. This will require a different response to each of the zones listed above and a different standard of comfort for each. It also requires micro-adjustment at the individual work station to meet each individuals specific needs. This is not your one-temperature-fits-all one-light-level-works-for-all approach. The goal is to have the feeling of an open building in a temperate climate.The task of the mechanical systems is to moderate the extremes of climate not to eliminate nature, variety or weather. | | One of the most important devises, for creating architectural space, is the use of the diagonal view in relation to a fixed, regular modular structure. Schindler was a master at this. It is as if another building exists within the first. Of course, it has to be designed to have this effect. The diagonal translucent roof, in this work, stresses the diagonal in a building that is otherwise fixed to the square form; it brings in 15, 30, 45 degree angles - both on the horizontal and vertical planes. It starts - on the North end of the building - as an idea, a suggestion - and becomes, at the South, the dominate form of the environment. It becomes the physical embodiment of a transformational process. The physical transformation of the building from it’s north side more-or-less “traditional” forms to the shapes housing the radiant Room is thematic [link], as well as, the reflection of utility [link]. | | Another strong aspect of this design is the treatment of prospect and refuge. For a building of its size, there are a great number of sub-areas each with a unique blend of spatial sensibility. This is enhanced by the almost complete dissolution of the distinction between “inside” and “outside.” This plays on the traditional in transition theme, as well as, constantly “turning” the viewpoint from the expected to the delightful. The building simple does not “behave” in the way that people have come to expect. While the building will have a great sense of shelter, and while it will be comfortable, it is not a structure that can be “taken for granted” - it cannot be ignored in the sense of being the same-old-same-old that everyone has seen a thousand times and, thus, blanks out of awareness. This building has to be approached as a fresh landscape is met. It demands alertness and participation. Your “find” your way and your own place within it. | | This article is entitled Creating Personal Workspace and you may wonder what all of the above has to do with this. Everything, of course. It is the intimate features of the design, how the building is built, the economic model upon which the design is based, energy strategies, architectural philosophy - that, as a sum - add up to the overall humanity and economy of the building. It is the way buildings are designed and realized that results in so few personal workspaces that actually provide the kind of work environment that most workers desire. It is not the competency of most of the players - nor their intent - that is at fault. It is the system [link] by which the work is done; an entrenched system that is not easily moved and is both closed and deeply defended. The price for a human workplace is not gobs of money; the price for a human workplace is the courage to build in a human way; and for that we need Cathedral Builders [link]. A building that will support the variability of human experience and desires is by definition a high-variety environment. The modern workplace, outside the showy but rarely used public places, is exactly the opposite of this; it is an essay in sameness - in conformity. Different people like different light levels, different views, different levels of exposure, different temperatures. Besides providing them a fair measure of control of these factors at their work stations, a human building offers a variety of spaces that are expressive of different kinds of ambiance. They are truly landscapes of experience. They satisfy the hunter-gatherer in us all [link]. | | The sub-title of this essey was Creating Urban landscape. This project addresses directly, just by its location, an extraordinary number of urban issues. How these are treated is important; it is the “answer” of this work which will be an unequivocal vote in one direction or another. It is a statement of the institution it represents and houses. One of the client requirements was that a STATEMENT was called for with this project. I agree with this. But perhaps the statement that should be made is different than the usual “architectural” one - all glitz and architectonics. I have named this building SYNERGY because, given its function, and given its thematic material, it is a synergy of what are, today, assumed to be opposing conditions, forces and values. These range from just what a proper workplace is, to what in the nature of an urban building, to how a project like this should and can be realized. These are not trivial concerns. One thing should be clear: the purpose of a system is its output. The system in place is doing its job. This system is what produces the workplaces we have today. Workplaces that are physically unhealthy; workplaces that do not support collaboration and the many forms of knowledge work; workplaces that are not based on either sustainable economic nor ecological realities; workplaces that do not honor, support, facilitate nor express human potential [link]. Yet, there are the environments where most spend the majority of the lives. The message is clear. If you want an alternative place to work, you have to seek an alternative way to build. | | What is unique about the urban landscape? Why is this an appropriate place to work? What is special about working here - not someplace else? These are the questions this environment has to answer. Failing to do so is just to plunk another box down on a dead street with no feeling for the setting other than it provides bearing for the footings. We must lean to see the the urban landscape as we would view a redwood forest or the Grand Canyon. We must be aware that we have to build into this landscape, adapting to it as we modify it by our actions. We must begin to see this process as natural - as an expression of human nature; as art; as the machinery of human enterprise and wealth-making; as the expression of our society and our ability to build our dreams. | | link: 3d Model • Link: Index of NavCenter Network Projects | | Institutions build to meet their own needs for facility. In doing so, they participate in the making of the urban landscape. The Urban landscape is made one piece at at time but its sum is greater than the addition of these individual works. The individual buildings accrue a negative or positive synergy. It is never static; it is deteriorating or building a greater whole. Each project, then, has to satisfy its unique mission and requirements - at the same time - contribute to the amenity of the greater social landscape. Armature is created as well as diversity [link]. Most building projects do not have the opportunity to significantly advance the greater urban landscape of which they become a part. This one does. Its location at the intersection of three distinct neighborhoods is one reason [link]. Another, is the time in which this project will be built. This neighborhood is in transition. The next moves in this process are of greater than normal significance. What is done at this corner is will help establish a course for the work of greater scope to come. Institutions, as social entities, intrinsically have the responsibility to think and act larger than themselves and to work in an extended time frame. They make the future. SYSNERGY is a small project as these things go; yet, it can have a significant impact on the course of this neighborhood. It has been designed to to do this without fanfare and exorbitant architectural tricks. It is a simple work of with a focus on intrinsic and timeless values. It is designed to become an anchor and catalyst - and a standard [link] - in a process that will take several years to unfold. | |  | 4 Projects explores both the value of creating a new urban workplace and the means necessary to accomplishing it. Link

to go to individual projects, click on pictures | | Matt Taylor

Calgary

June 14, 2003 |

SolutionBox voice of this document:

ENGINEERING • STRATEGY • PRELIMINARY |

posted: June 14, 2003 revised: July 30, 2003

• 20030614.424409.mt • 20010706.220987.mt •

• 20030708.222200.mt • 20030709.233210.mt •

• 20030730.376298.mt • (note: this document is about 65% finished) Copyright© Matt Taylor 2003 | |

|