click on the dome to view video of the 2009 Exhibit |

|

| Page One is a SCAN of the Exhibit with my thoughts while there and during the month following my visit. My purpose here is to set the context for a formal criticism [ page 2 - Focus] and recommendations for future like works as well as the continuing development of the Guggenheim itself [page 3 - Act]. As with any scan there are no answers - only observations which may lead to useful questions to be followed up with on Pages Two and Three. |

|

| |

|

| In 1943, Frank Lloyd Wright started design on what would become his most controversial, complex, greatest and compromised creation. No other client work occupied his attention for so long nor required as many revisions. Between his first design and the Guggenheim’s completion, six months after his death, he and the Taliesin Fellowship executed a number of projects which exceeded Wright’s most productive periods. Many of these, the VC Morris Shop as example, were influenced by the Guggenheim and in turn influenced it. |

| Mr. Wright had the ability to absorb architectural ideas quickly, from many sources ancient and contemporary, and make these uniquely his own turning them into something entirely old and new at the same time. I believe, however, he was his own greatest influence. He would work and rework projects, built and un built, for decades bringing the past forward and taking the present back to the past. He saw all of his work as a single piece just as he saw every element of a single building as a whole piece. He also responded to the work of his contemporaries far more then has been commonly recognized. |

| The debates raged over the guggenheim long after Wright’s death and their echo can still be heard to this day. The full story of this titanic struggle, in the worlds of art and architecture, has never been fully written and perhaps it never can be. In a way these old battles do not matter so much as before. The building can speak for itself and it may be best to let it do so without too much discussion of what it might have been or what others did to it along the path of its making and use. It seems to me that this exhibit is a significant step toward reconciliation of old battles which no one actually won. |

| The making of architectural art is not a simple thing and it cannot end, as is the default practice, with “finishing” the building. The work evolves and mutates for decades; on occasion for centuries. Rarely, these changes are organic and an improvement making a better fit between building, occupants and planet. The typical case is a slow decline to ruin. Once in awhile, a great work is restored repurposed and brought back to life. |

| Often this decline is driven by the chronic real estate boom-bust cycle which, while profitable for a few, is wasteful of human capital and devastating for our environmental balance sheet. In the U.S., a mayor building, loved when it was built, can decline and be torn down in 40 years or less. Most often, great works are not even granted the mercy of deliberate destruction. They are carved up and mutilated - left to suffer slow bit by bit outrage in the hands of future owners who have no idea why or how they were built in the first place. Great architecture deals with the utility aspects of a building very well yet the real purpose of it goes far beyond these considerations. Architecture is an art like no other. It is left out in the rain and subject to changes which no sane person would impost upon a painting, symphony or play. |

| When a masterpiece does, by some mysterious yet-unknown-process, become fit - and remains so - with its social economic and ecological environment, we are shown a successful work of architecture and given a sense of what a viable approach to the practice of planetary architecture can become. The necessity for learning the lessons for knowing and developing the practice processes necessary to bring this about on a global scale have passed beyond nice-to-have to critical. In the time from when the Guggenheim was built to now we have, as a species, thrown away a large portion of our time margin for successfully adapting to the future we ourselves a creating by default. On our present course, sometime in the future, our planet may be another museum of the remains of one more species who failed to meet the challenge of planetary design. |

| Frank Lloyd Wright did not conceive of architecture as was the norm a half century ago nor as it is now. This was the essence of the debate regarding the Guggenheim, not the tilt of the paintings, light source disputes, the intended overhang over the sidewalk, and other such matters. His master was Louis Sullivan whose influence, while always noted, was I believe much greater than has been commonly recognized. I also believe that even including the many travails Wright experienced in his career, the slow death by work starvation of Louis Sullivan had a far greater impact on him than even his own experiences. The last 20 years of Wright’s life were notable for the number of works he produced and the hunger with which he pursued each opportunity. A prolific as he was - amazingly so - this was an artist who did not get it all said and who was, at the eve of his death, beginning a totally new “fourth” phase of his work. With all of the successes of his last two decades, Wright’s un built works were among his best. What remained in his mind, not drawn, may have eclipsed all of it. |

| Mr. Wright was criticized for the amount of work he took on in the last period and also for some of the works he produced. It was claimed he violated his own principles and was reaching for “gesture” - that these were exaggerated statements unrelated to function. This criticism remains in place, amazingly, after several decades of post-modernism and whatever it is we can call the signature pieces being produced today. If anything, it can be argued that Wright, once again, plowed new ground and produced work which was predictive decades into the future. This was done without a portion of the means which are available today. The Guggenheim and the many un built projects profiled in this 50 year celebration, while still fresh and provocative, would not nearly be as shocking to the public as the Guggenheim was at its opening. It is interesting, and important, that many of the un built projects beautifully presented at this show are those who critics in the past delegated to relative obscurity as examples of Wright’s declining years. I was there. There was nothing declining about it. |

| Wright apprenticed to Sullivan starting on the Auditorium building which reflected an era and place where grand works where built with detail, craftsmanship and civic support almost impossible of to conceive of today. Even by the time of the Guggenheim, there was a material difference in how a major structure could be rendered. Sullivan started out building large projects and ended his years building a few, small yet masterful works. Wright, with a few exceptions, was a domestic architect. His un built projects: San Marcus on the Desert, Crystal City, the Steel Cathedral, Hunting Hartford, Pittsburgh Point, Baghdad, the Mile High Illinois, were unrealized and often treated as fantasy works - unworkable and not serious. Only fragments of Broadacre City were realized. Wright produced many advanced concepts of the skyscraper, from the teens to the end of his life, yet built only two small yet important works. The ideas he proposed, radical at the time, are common now although in too many cases rendered without understanding of the underlying principles. This is a great loss. Works of the scope and nature of Wright’s large un built projects are done today. Many are fine examples of architecture yet it is safe to say that wright’s would have held their own, if built. This is one thing I believe the exhibit made abundantly clear. |

| It is a fair criticism to say that the later, larger commissions built in his last years: The Tower, Guggenheim and Marin County Center, lacked the finish of the Sullivan era, his 0wn early work and even his late domestic pieces. I think there were four causes of this: budgets, unlike the far more generous ones at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 21st Centuries. The volume of work at the end which was accomplished by, essentially, a 20 man office at Taliesin. And, Wright and his many associates, over 70 years, had a long time to work out the grammar of traditional materials while including the innovations of the first 30 to 40 years of the 20th century. Post WWII, and at an increasing rate afterward, technology innovation soured while craftsmanship declined. The Usonian Houses, a brilliant synthesis of materials, methods, floor plans and details, created a true middle class work of art but would be an expensive house to build today well out of the range of the average home owner. The craft base which made these masterful houses possible is largely gone. Wright’s later public works pushed technology as far as it would go and now and then further then it was ready to go. The grammar of these later works was never developed to the degree that the work from 1890 to the mid 1930s was. A few more years and a dozen larger projects would have afforded this. |

| To this day, modern materials and construction means still constitute a profound architectural problem when you consider texture, touch-ability, connotation, person-friendliness, and in many cases, durability and weather-ability. Modern materials photograph well - far better than they touch. They fail to age gracefully and resist repair. It was interesting to me that the Guggenheim, which had just undergone an extensive restoration of which a great deal of the focus was on the concrete, had several surfaces on the ramp rail which are pealing off. And, the aluminum windows and doors are the less appealing features of the building. The color-texture synthesis with the concrete is not good. In the 1890s up to WWI, these window and door frames would have been bronze. |

| One of the criticisms of the Guggenheim, when built, was that it did not fit into the urban environment. A building can be radically different in form and still fit into it’s context. I argue that softer edges, a slightly wet sand color finish, more landscaping around and on the building, the top ramps overhanging the sidewalk as intended, all would have placed the Guggenheim much more comfortably in it’s setting. The overhang was a big code issue at the time. It is interesting to note that upon leaving the Guggenheim and returning to my hotel, I saw a new construction with a cantilever boldly projecting over the sidewalk. The rule is relaxed now. The Guggenheim is still somewhat uncomfortable with it’s setting and the city with it. This does not have to be. With a few alterations, the building can fit marvelously into the New York City landscape. |

| This controversy, and it’s partial resolution, has a great deal to say about how the practice of architecture is carried out. It is easy to point fingers and blame individual players in a complex social process yet it is important to realize it is the system by which architecture is created which is the villain - a system and process so ubiquitous and embedded in our social consciousness that most are totally unaware it exists, unknowing of the damage it does, and not willing, when confronted with it’s consequences, to take the actions necessary to build a true method. |

| The process by which a major building is made cuts across many domains of human endeavor effecting nearly every aspect of life. The economic and ecological impact of a building is significant. The cost of keeping a building in use far exceeds its initial capital expense. The effort required to achieve a successful result is high - to make a great work of art boarders on the heroic. Given these costs, it makes no sense to me to do other than make every building built the best it can possibly be to be kept and improved over lifetimes. We do not do this today and we are less for it. |

| Architecture is not a visual art it is a fact-based experiential art the consequences of which cannot be ignored. It’s impact is long term and ubiquitous. It matters not if a building be a simple home or the most expensive building in the world. Each deserve full attention, our best effort and total integrity. This is not considered, generally, to be practical. Yet, ask if what we are doing to this planet, ourselves and our fellow creatures is practical. I think not. Nor did Sullivan or Wright. |

| Wright’s work was not based on esthetic, style, formula or dogma. Yes, his personal stamp as an artist was present in his works yet this was not the essence of them or even what mattered most to him. His work was based on a way of life; a concept of Nature, a hope for a truly democratic society. To understand this, even now, it is necessary to spend time living in and working in an environment build on the principles he and Sullivan advocated and, even with their genius and dedication, only began to make real. As I walked through the Guggenheim, I wished that each person there could first spend a weekend in a Usonian like the Rosenbaum House so that the drawings, Models and multimedia could become sensible. Then the difference between Wright’s vision and the world we have built could be understood. |

| I end with a quote found on page 122 of Frank Lloyd Wright in New York. Many will take this statement of Wright’s as posturing or bombast - or colossal ego. I do not. I knew the man, and then mostly as an observer, only in his later years. In this regard, while he immensely enjoyed playing and being Frank Lloyd Wright - and while he was certainly using his fame to promote architecture as he loved it - the man I knew was the distilled essence of 70 years of architectural practice. Wright was a working architect to the very end. He had a far better grasp of himself - strengths and weaknesses - then is generally believed. He knew what he had done and also what remained unfinished. This is what he said in 1957: |

|

I consider myself a success

only insofar as my life

is useful, revealing, and rewarding to my kind.

Who knows who is a success until long after the circumstances?

Success is measured

not in ordinary terms,

but what will transpire

fifty years later.

So fifty years from now,

you will know whether or not

I am a successful person. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

VC Morris Shop looked back to the 19th Century and Louis Sullivan and forward to the Guggenheim which would not be completed for another 10 years.

It’s detailing and finish indicates the kind of look that Wright expected for the Guggenheim and in my mind would have made a profound difference in the over all scale, feel and amenity of the building. As a shop for decorative items, and now for Xanadu craft arts, VC Morris presents the pieces in a natural way encouraging a leisurely browsing on the part of the customer. This shop challenged retailing as much as the Guggenheim challenged the concept of the museum although Wright’s influence on museum architecture has been significantly grater than on retailing.VC Morris was not nearly as challenging as the Guggenheim, structurally, and as a building process. It was built much as Wright had been building for over 50 years. The finish is more typical of Wright’s larger body of work. The ramp works very well in the Morris Shop as it does in the Guggenheim. Morris is more intimate, of course, however the space created is impressive given the scale of the building. Prospect and refuge is in better balance in Morris although I see no reason why this cannot be accomplished just as well at the Guggenheim if the appropriate changes were made. The Guggenheim exhibit was well done in terms of the choice and preparation of the pieces themselves. The space easily handled, without crowding, the great number of people who came to see the excellent drawings, models and multimedia yet, even in his own building, that special quality which is a Wright environment was lost.

I think that this gets to the heart of what the conflict between Wright and the art and museum world was really about. The drawings and models were displayed but they were not presented in a way which Wright would have placed his own work in his own environment . On a broad scale they can be scanned from walking the ramp and viewing across it - one of the strongest features of the building. However, on the human scale, the displays did not relate to the building nor it to them and those viewing could only do that - shuffling from one idea to another without reflection. What is missing is clusters of sitting, plants, shade and shadow, variable light, opportunity for contemplation and dialog - all conspicuously absent from modern social intercourse. This separation of human from the displays created a barrier between the person perceiving and the object perceived. Despite all effort, the most important aspect of Wright’s work is absent. |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

GoTo: VC Morris Shop for my description of this San Francisco Jewel |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

Five books which, if read synoptically, provide an interesting context for understanding many of the nuances of this 50 year anniversary event. Many aspects can be seen that are different about our society from Mr. Wright’s time - at time which spanned from the aftermath of the Civil war to the dawn of the space age. They also reveal differences in attitude, among the public as well as architects, by which architecture was conceived, practiced and used. Revealed also are attributes of Wright’s persona which many have criticized without fully understanding these “paradoxes” in relationship to his time, the challenges he faced, and most importantly his creative process.

Two of these books were written in conjunction with the exhibit: the Guggenheim and Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of the Modern Museum; and, Frank Lloyd Wright From Within Outward. They are top quality: informative, comprehensive, objective and balanced. Together they provide an outline of the making of the Guggenheim and of Wright’s seven decades of practice.

While acknowledging the controversies surrounding the design and pointing out the positions of the various players in the scenario, the authors came to the conclusion that the very changes presented by the building’s deviation from long established museum practices became, over time, a catalyst for the making of numerous shows of outstanding creativity. The Wright design was not a passive background that kept the rain off the paintings, it forced a dialectic between building and curator which, when embraced, produced a greater result than either alone.

This was central to Wright’s practice and concept of architecture. He was accused often of ignoring client’s requests. The popular myth is that he built what he wanted while running over his client. These are ignorant statements. I do not say this in a pejorative way. I mean it literally: repeated statements not based on reality that became urban myths often repeated by people whose training should have encouraged them to investigate further. In 1958, when I was at Taliesin, and the Guggenheim was being built, I took it upon myself to check this myth out. I did this by looking in the vault at original drawings - some that were in this show- going back to the beginnings of Mr. Wright’s practice. I also talked to several of his client’s who had lived a number of years in his buildings. The vault revealed multiple designs for clients until the one was found that satisfied both client and architect. The dialogs revealed - again and again - that “Mr. Wright did not design a house for who I was but for who I could become.” Wright designed transformational environments and that was the essence of his art.

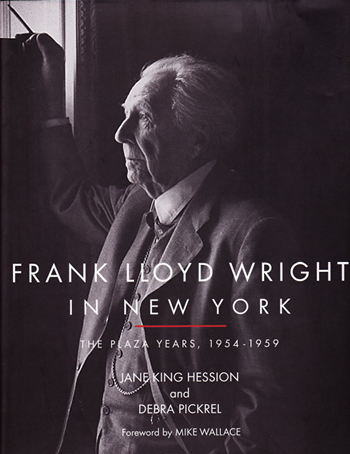

I add to this syntopical mix, Louis Sullivan His Life and Work, On and By Frank Lloyd Wright - A Primer of Architectural Principles and Frank Lloyd Wright in New York - the Plaza Years 1954-1959. These provide important information and insights about Wright’s relationship with Sullivan, the modular order in his work, which until the 80s his critics refused to recognize, his complex relationship with New York City and his relationship with contemporaries from many walks of life.

Mr. Wright was a complex man. He mined the past as well as the future. He lived at Tailiesin and the Plaza. He sought to bring the two together as a continuity. He played the game with gusto yet never lost sight of nor sacrificed the outcome. In this, he was the most authentic man I have ever met. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

FLlw:

“What a man does... That he is”

|

|

| The Guggenheim is an extraordinary architectural concept which is flawed in its execution from final design to building and use. Compared to many other Wright creations, the fidelity of the concept-to-reality process was greatly compromised. In terms of client understanding and the stewardship of the building in it’s early years, compared to the Johnson Wax Building as example, it was a near failure which has over the decades been partially redeemed. |

| If this sounds like hash criticism it should not be taken as such. These are just the facts and Mr. Wright himself was well aware of what the initial outcome would be. I witnessed this awareness in the Taliesin drafting room one day in the Spring of 1958. This is a story I will relate in Page Two of this documentation. In the final analysis, however, all things considered, the only fair judgment possible - a judgment including all the players, friend and foe of the project alike - is “Well Done!” The Guggenheim was built. It has inspired a generation of museums. It has become an integral part of New York City. It still challenges, provokes, amazes and shelters. It is stewarded with loving care. It has paid back its investment many times and shifted the idea of what a museum is. What more can be asked? |

| Wright’s large scale projects, mostly not built, of the last two decades of his practice were deliberate explorations which pushed the state of the art not only structurally but also the use of materials and often the traditional view of the functionality of the building itself. Many perceived Wright as a 19th Century advocate of the old values. When Democracy Builds, for example was generally perceived as a Victorian rant against cities, progress, capitalism, the modern, and just about everybody. Others saw Wright on the extreme future edge of science fiction proposing fantasy projects like the Illinois Mile High - impossible to conceive the use of, pay for and build. Yet, today if you read When Democracy Builds, an objective evaluation can only conclude that Wright’s perceptions were prophetic of much of our currant situation. And, there are many projects in proposal and development today that are equal to the scope and scale of the mixed-use Pittsburgh Point Park Civic Center Project including several mile high building proposals like the Illinois [admittedly, these are on hold with the present financial crisis and the melt down of Dubai - come back in a few years]. Where was Wright in the continuum of the Civil War to the Space Age? Where is the Guggenheim in this continuum? In the U.S. we tend to build major buildings and tear them down in 25 to 40 years. In Europe they tend to keep and reuse buildings for centuries. If we think of the Guggenheim as a structure which will be alive and viable 200 years from now is it unreasonable to understand that it’s first 50 years are but the natural maturation of youth? |

| The Guggenheim got built. This was extraordinary for it’s time and would be remarkable even today. It is an example of an approach to civic architecture which, once common, was fading in the 50s and may yet return hopefully free of bombast and unnecessary controversy. It is the creation of a man born just after the Civil War who at his moment of death was still building a vision which remains ahead of us - a vision only we can shape and realize. |

|

| The first thing which should be said about the exhibition is that it was a gracious and healing act. The exhibit was called Frank Lloyd Wright FROM WITHIN OUTWARD - it could have as rightfully been titled Frank Lloyd Wright COMING HOME. It is said that Frank Lloyd Wright hated cites and New York City in particular. It is overlooked that Broadarce City was a city. Wright loved New York and he loved to hate it. He was drawn to it as any talented, intelligent person was then and today: in Jane jacobs’ term (replacement) cities are where it happens. Wright also was born to a Welch family of farmers, teachers and preachers. He believed in living with the land and Nature. Taliesin was not an accident. Rather than being inconsistent, Wright was totally consistent from the valley of the god almighty Joneses to Chicago to Taliesin to New York. Broadacre city was not a preamble to that spreading monotony called suburbia. It was a synthesis of Taliesin and New York. He wanted the best of both without the flaws of either: |

“Seen at night, heedless of real meaning, the monster aggregation has myriad, haphazard beauties of silhouette and streams with reflected or refracted light. Undefined, the monster becomes rhythmical and appeals to what remains of our universal love of romance and beauty. The immense aggregation becomes mysterious and suggestive: inspiring to the ignorant. Fascinating entertainment, this mysterious gloom which hangs necklaces of light through which shines clouds of substitutes for stars. The streets become rhythmical perspectives of glowing dotted lines, reflections hung upon them in the streets as the wisteria hangs its violet racemes on the submerged trellis. The skyscraper, in the dusk, is a shimmering verticality, a gossamer veil. a festive scene-drop hanging there against the black sky to dazzle, entertain and amaze.

“The lighted interiors come through it all with a sense of life and well being. At night the city not only seems alive. It does live. But lives only as all illusion lives.”

Frank Lloyd Wright

1945

When Democracy Builds

pp. 27-28

|

|

| After decades of conflict and mutual love-hate, New York invited it’s most persistent and serious critic to come back to stay - a long awaited reconciliation; “a very close collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.” |

| The exhibit was excellent in every way with the exception I have noted that the building, drawings, models and media failed to become an engaging, interacting environment for those who came to experience the essence of the man and his art. I will explore this at a more technical level on Page Two of this documentation. I observed that many who came to see remained confused by what they saw and read. It is my work experience that if the exhibit had focused on the total gestalt of the experience of the place, the more cerebral aspects of drawings, models and words would have been much easier to comprehend. Wright’s goal for the Guggenheim was only partially realized; but then, there is the next 50 years. |

|

| The MG Taylor method of Syntopical Reading was inspired by Mortimer Adler and his work on the Great Books of the Western World and outlined in How To Read a Book. The idea is to read several books, together, to query the authors and engage them in a dialog. We have several ways of employing this idea in our processes. The simplest is for a team to have each member take a book, read it and become the author in a interactive process with other members of the team. First, each “author” explains what their book is about, why they were compelled to write it, what they learned while doing so and how they think it bears on issues, opportunities and challenges of the team. After each author has reported, without interruption, except for questions for clarity only, then a focused dialog follows: what is similar and different about the different author’s views? What new insights are found by the convergence and divergence of these views? What are the significant points in relationship to the team’s purpose and work? These questions should be discussed without closure or forced agreement. At the end of this second step, the dialog takes what has been harvested and applies it to a set of questions instrumental to the team’s learning and work. Last, these questions are answered or, if not possible, a process is identified to get them answered along with assigning other relevant action steps. |

| The five books, I have introduced, compose a rich resource not only about the Guggenheim, Wright, architecture and its practice, but also about creativity in general and the social processes which augment it or thwart it. Together, they tell a story that each could not tell alone. They place Wright, the Guggenheim, and modern architecture in history - a history which is still playing out. Answers for today will not be found in these books nor will they be found in the Guggenheim or Wright’s work. It is the experience held in common by the entire team, who reads and dialogs on this material, and then applies this experience by design to real projects that value will be created. |

|

| Asking the right questions at the right time is a fundamental yet often overlooked skill in the exercise of design and creative endeavors of all kinds. In looking back upon an effort, it is often more useful to ask what questions were apparently not asked rather than challenge the decisions which were made based on the perceptions of the time. With this questioning, it is equally important for all members of the process to mutually define the scope of the problem being solved. With the Guggenheim project, this was clearly not realized at the time of it’s creation but it may be argued that this gap has closed somewhat in the last half century. To apply any learning to today’s work, it is essential that be an agreed upon context for those engaging in the exercise. |

| Questions I think were not adequately defined during the first cycle of the Guggenheims design-build-use process and are useful for producing works of like-kind as well as for successful stewarding of the Guggenheim are: |

How can the arts: architecture, painting, dance, theatre, sculpture, music, media, performance, be better integrated, preserving individual integrity and creating syntheses and synergies?

How can art be protected and preserved yet experienced in a way which in itself does not impose a separation of the art from those who would understand and enjoy it?

What is the role and proper scope of a museum in the 21st Century and how can it be made relevant to a world of many cultures?

How can art, without debasing it or making it a dead object hanging on a guarded wall, become an integral aspect of individual’s lives and cultural experience?

How can the many fields of expertise and their practitioners collaborate - not combat or merely cooperate - in the making of the public experience of ART?

|

| What is the next level of human aspiration and expression? How can public art reveal it? |

|

posted:

August 23, 2009 • updated November 12, 2009 • pages 2 & 3 are in progress and will be posted shortly |

SolutionBox

voice of this document:

INSIGHT • POLICY • PROGRAM |

|

click on graphic for explanation of SolutionBox |

|

|

work in progress |

|

|

|

Guggenheim 50th page 2 |

Guggenheim 50th page 3 |

postUsonian Project |

VC Morris Shop |

|

work in progress

piece being reformatted |

work in progress

piece being reformatted |

|

Planetary Architecture |

Syntopical Reading |

Architectural Practice |

a Future by Design... |

click on icons to go to postings |

ARTS

Guggenheim Museum Turns 50

As it turns 50, the Guggenheim in New York City remains a radical model for an art museum

Nicolai Ouroussoff, The Times's chief architecture critic, takes a retrospective look at the museum |

|

| GoTo: The Sydney Opera House |

|

|

|

|

© 2009 Matt Taylor text and photos • book covers are copyright of their respective publishers • video clip image copyright New York Times |

|

|

|

\\\\\\\\\

|